The cure for pain is in the pain.

Good and bad are mixed. If you don't have both,

you don't belong with us. - See more at: http://allspirit.co.uk/rumilovers.html#sthash.DLUmUn3q.dpuf

The cure for pain is in the pain.

Good and bad are mixed. If you don't have both,

you don't belong with us. - See more at: http://allspirit.co.uk/rumilovers.html#sthash.DLUmUn3q.dpuf

The cure for pain is in the pain.

Good and bad are mixed. If you don't have both,

you don't belong with us. - See more at: http://allspirit.co.uk/rumilovers.html#sthash.DLUmUn3q.dpuf

The cure for pain is in the pain.

Good and bad are mixed. If you don't have both,

you don't belong with us. - See more at: http://allspirit.co.uk/rumilovers.html#sthash.DLUmUn3q.dpuf

I think people in general have a tendency to overlook their own

emotions. Either you dislike what you're feeling, so you try to

distance yourself from it; or you feel too busy to deal with it; or you

can't make sense out of it, so you try to tell yourself, "There's no

reason for me to feel that way." But I disagree. There is always a

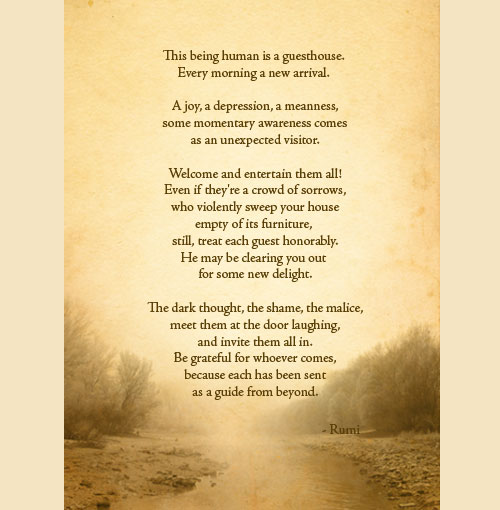

reason for every feeling, even if that reason is subconscious. However, whether or not you understand the origin or reason behind every feeling doesn't entirely matter. One of the fundamentals of Rumi's philosophy is that all human emotion serves a purpose. Feelings are neither arbitrary nor meaningless. Every yearning, every desire you have exists so that you will seek out the things you really need--not only to live, but also to be a complete human being. We feel hunger so that we will eat. We feel tired so that we will sleep. We yearn to be creative and express ourselves because we need to create things. We yearn for God, for a higher spiritual order, because we need to make spiritual sense of our universe. It is not enough to just exist. We must know why. We must feel there is a purpose to our being.

I'm not saying that simply wanting there to be a God is a justification for believing in God. I think Rumi's idea is that, if there is a yearning, there must be an answer to that yearning. If we are thirsty, we must drink. No one would deny this. But does it not logically follow then, that if someone deeply longs to make music, they must make music? Why is it that so many famous artists throughout history have been destitute, starving, cast out of society, and yet somehow felt overwhelmingly compelled, not to seek out a decent paying job, but rather to make art? As Vincent van Gogh said in a letter to his brother, "Sometimes I draw . . . almost against my will, but it is a hard and difficult struggle to draw well." Why on earth would he choose to spend his time doing such a seemingly fruitless activity, when he lived in extreme poverty and only sold one painting in his entire lifetime? Because he had a hunger that needed to be fed: a hunger as real and demanding to him as any physical hunger.

This is where it gets difficult, I think. Everyone understands hunger, thirst, and tiredness because we all feel it in essentially the same way. But not everyone feels the need to draw, or play sports, or commune with God. Some people feel these yearnings so powerfully that it drives their entire lives, while others might feel that same yearning not at all. Still more people might feel a moderate amount of this or that desire, but not to the point where they would make such sacrifices as van Gogh did. When it comes to non-physical needs, it takes a great deal of empathy and patience to understand what drives people to do what they do. However, like Rumi, I believe that nothing we feel is without significance. Although making music, writing a story, or playing a sport might not be essential to life in the physical sense, it is essential in the spiritual sense. It is not water for our bodies, but for our souls. Whatever you do that makes you feel most truly happy and whole, that is your purpose in life. The trick is that it's up to you to find the right balance of these things in your life, and to be strong enough to insist on the things you need, even if other people don't understand them.

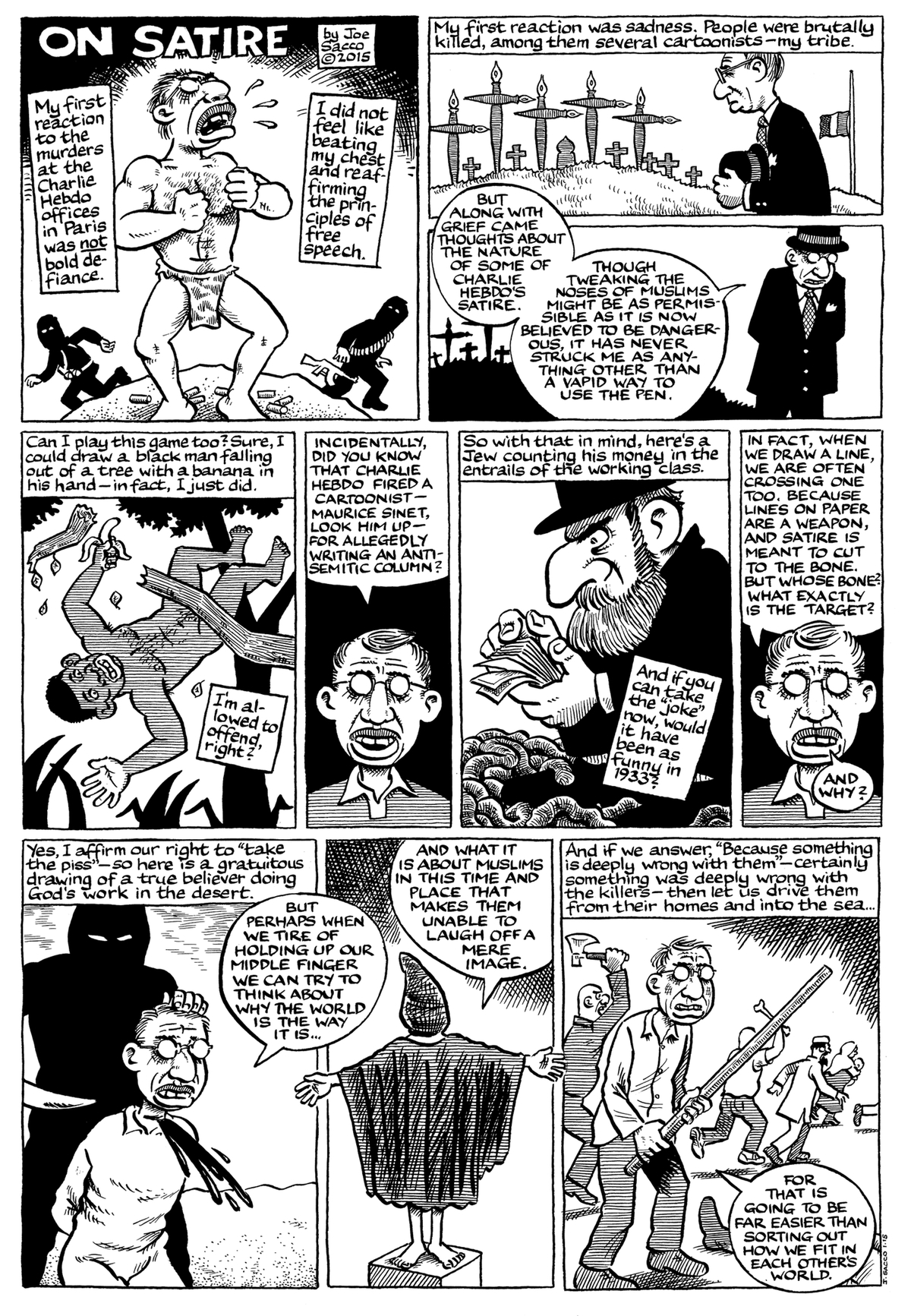

Of course, then you must ask, what if you yearn to do something wrong? What if the fruition of your desire would be harmful to other people, or even to yourself? Obviously you can't just use the excuse that you wanted to do it, so therefore it must be right. Our feelings and our desires need to be interpreted, balanced, and acted upon in a constructive way. An emotion may be leading you towards the right place, but you must interpret it correctly and find the right way to get there. Not all pathways to an objective are equal. For example, if you feel that a situation in your life is getting alarmingly out of control, perhaps your first impulse would be take control of it through violence or intimidation. That impulse is not the feeling you should follow. What you really need to ask yourself is, what is upsetting to me about this situation and how can I fix it in the most effective, benevolent way possible? Violence just leads to more violence, and running away from the situation just leaves it to be solved another day. But if it's upsetting to you, that means it needs to change, and there is probably a decent way to fix if you just think about it. I'm not saying that making that change is always easy, or that you can always do it without upsetting anybody, but most of the time, there is probably a constructive path that will lead you to what you really need.

Life hurts sometimes, but that pain only exists to tell us what we need. Rumi said, "The cure for pain is in the pain." It is a guide sent to lead you towards goodness and happiness. Even if you are lonely or feel unfulfilled, don't run away from that feeling. Don't ignore it. Follow it.

"That hurt we embrace becomes joy. Call it to your arms where it can change."

We can only change when we recognize our problems and decide to face them. If you feel broken, lost, empty, don't drown yourself in obligations and distractions. Follow your grief to the place where you can be whole.

The cure for pain is in the pain.

Good and bad are mixed. If you don't have both,

you don't belong with us. - See more at: http://allspirit.co.uk/rumilovers.html#sthash.DLUmUn3q.dpuf

~~~~~~~~~~~

One night a man was crying,

Allah! Allah!

His lips grew sweet with the praising,

until a cynic said,

"So! I have heard you

calling out, but have you ever

gotten any response?"

The man had no answer to that.

He quit praying and fell into a confused sleep.

He dreamed he saw Khidr, the guide of souls,

in a thick, green foliage.

"Why did you stop praising?"

"Because I've never heard anything back."

"This longing

you express is the return message."

The grief you cry out from

draws you toward union.

Your pure sadness

that wants help

is the secret cup.

Listen to the moan of a dog for its master.

That whining is the connection.

There are love dogs

no one knows the names of.

Give your life

to be one of them.

~Rumi

Sources of inspiration for this post:

The Illuminated Rumi, translated by Coleman Barks